28-29th, November, 2023 | Australian National University, Canberra

The purpose of this tutorial is two-fold:

To illustrate how to solve a system of PDEs where one of the unknowns lives in (as opposed to ), thus requiring the construction of a div-conforming finite element space (as opposed to a grad-conforming finite element space).

To showcase the dynamic Adaptive Mesh Refinement (AMR) parallel distributed-memory capabilities provided by GridapP4est.jl. To this end, we will solve a system of PDEs featuring a multi-scale solution where the use of these techniques is particularly beneficial from a computational point of view.

We consider as a model problem the so-called Darcy equations, which can be used as a physical model of fluid flow in porous media. The PDE problem reads: find the fluid velocity , and the fluid pressure such that:

with being the outwards unit normal vector to the boundary , and the so-called hydraulic conductivity tensor. The first equation is known as Darcy’s law and was formulated by Henry Darcy in 1856; the second equation is the mass conservation equation.

In this particular tutorial, for simplicity, we consider the unit square as the computational domain. Besides, we consider pure Neumann boundary conditions, that is, the Neumann boundary is the full boundary of , and is the empty set (i.e., no Dirichlet boundary condition). Finally, we consider the hydraulic conductivity tensor to be just the identity tensor. In any case, we stress that the general version of the equations stated above are also supported by Gridap.

The source term in the mass conservation equation and the Neumann data are chosen such that the exact (manufactured) fluid pressure is:

Besides, using Darcy's law (i.e., first equation of the system above), we manufacture .

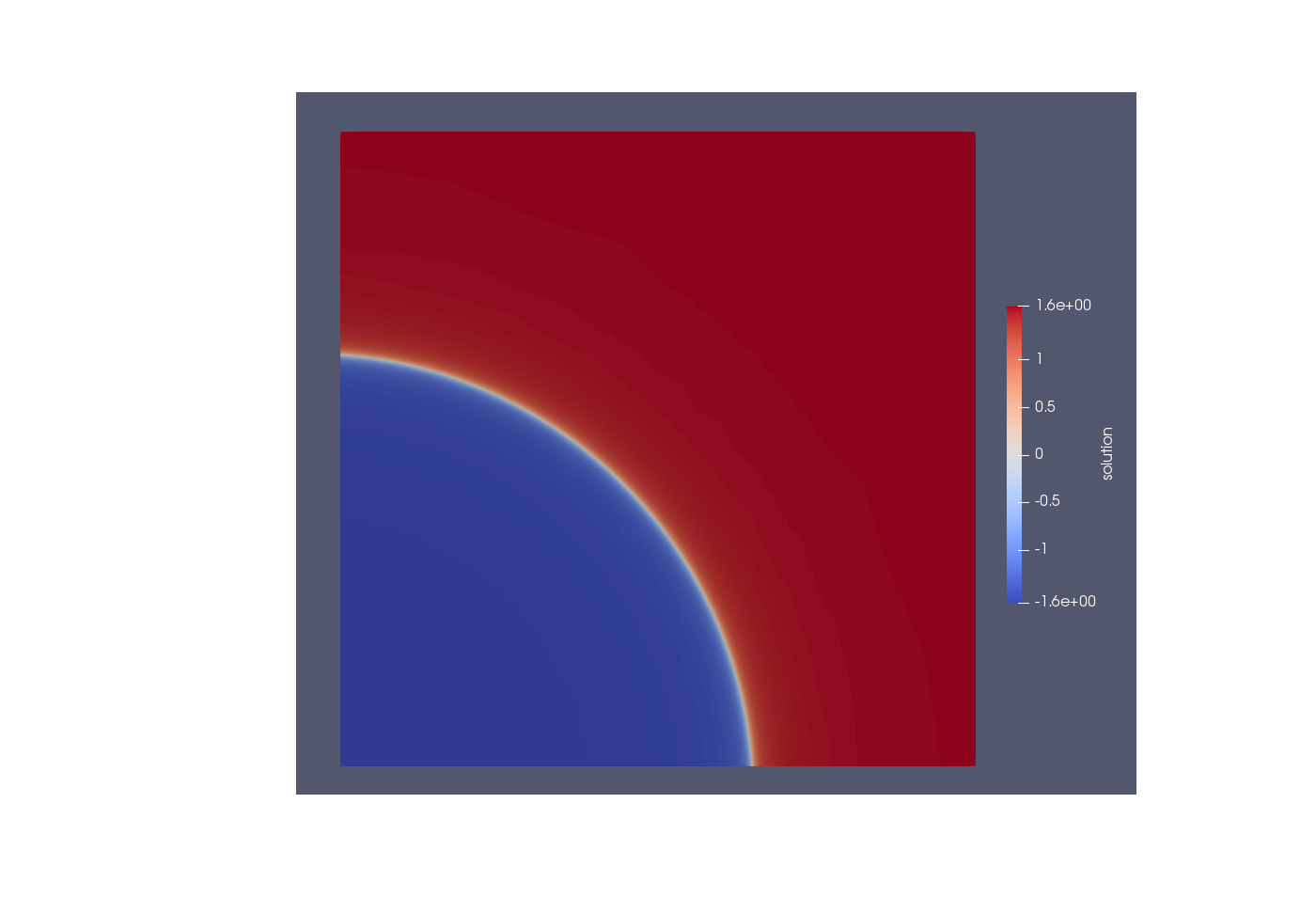

The solution has a sharp circular wave front of radius centered at . For example, for the combination of parameter values , , and , looks as in the picture below:  As a consequence of the multi-scale features of this solution, uniform mesh refinement techniques can only reduce the error at a very slow pace with increasing mesh resolution, and thus are very computationally inefficient.

As a consequence of the multi-scale features of this solution, uniform mesh refinement techniques can only reduce the error at a very slow pace with increasing mesh resolution, and thus are very computationally inefficient.

We denote by the space of vector-valued fields in , whose components and divergence are in . With this notation, the weak form of our problem reads: find such that for all , where

This weak form was obtained from the strong form as usual, i.e., multiplication by suitable test functions, and integration by parts in order to transfer derivatives from trial to test functions to reduce the regularity constraints on the weak solution.

In this tutorial, we use the div-conforming Raviart-Thomas (RT) space of polynomial order for the fluid velocity approximation, and a discontinuous space of cell-wise polynomials of order in each spatial dimension (denoted as ) for the fluid pressure approximation (see [1] for specific details). This pair of finite element spaces form a so-called discrete inf-sup stable pair. This mathematical property guarantees that the discrete problem is well-posed, i.e., it has a unique solution.

In this tutorial we leverage a more clever/efficient domain discretization approach provided by GridapP4est.jl. In particular, we will used a particular Gridap's DiscreteModel that efficiently supports dynamic -adaptivity techniques (a.k.a. AMR), i.e., the ability of the mesh to be refined in the course of the simulation in those regions of the domain that present a complex behaviour (e.g., the internal layer in the case of our problem at hand), and to be coarsened in those areas where essentially nothing relevant happens (e.g., those areas away from the internal layer).

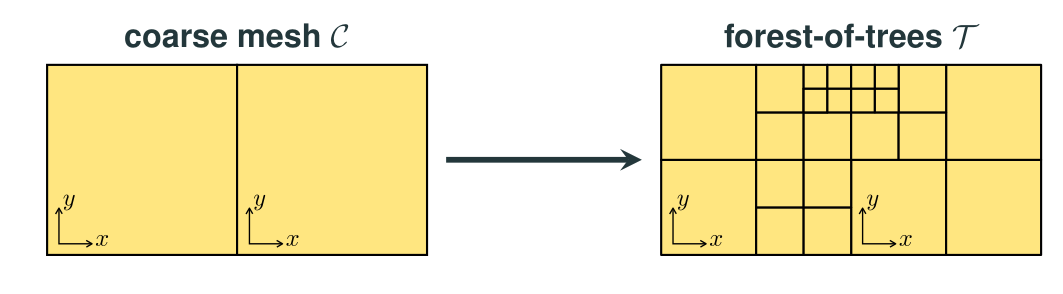

In order to support AMR techniques, GridapP4est.jl relies on the so-called forest-of-trees approach for efficient mesh generation and adaptation as provided by the p4est library [2]. Forest-of-trees can be seen as a two-level decomposition of , referred to as macro and micro level, resp. In the macro level, we have the so-called coarse mesh, i.e., a conforming partition of . For efficiency reasons, should be as coarse as possible, but it should also keep the geometrical discretization error within tolerable margins. For complex domains, is usually generated by an unstructured mesh generator, and then imported into the program using, e.g., using GridapGmsh. For simple domains, such as boxes, a single coarse cell is sufficient to resolve the geometry of . On the other hand, in the micro level, each of the cells of becomes the root of an adaptive tree that can be subdivided arbitrarily (i.e., recursively refined) into finer cells.

In the case of quadrilateral (2D) or hexahedral (3D) adaptive meshes, the recursive application of the standard isotropic 1:4 (2D) and 1:8 (3D) refinement rule to the coarse mesh cells (i.e., to the adaptive tree roots) leads to adaptive trees that are referred to as quadtrees and octrees, resp., and the data structure resulting from patching them together is called forest-of-quadtrees and -octrees, resp., although the latter term is typically employed in either case. The figure below shows a forest-of-quadtrees mesh with two quadtrees (i.e., ):

Tree-based meshes provide multi-resolution capability by local adaptation. The cells in the mesh (i.e., the leaves of the adaptive trees) might be located at different refinement level. However, these meshes are (potentially) non-conforming, i.e., they contain the so-called hanging vertices, edges, and faces. These occur at the interface of neighboring cells with different refinement levels. Mesh non-conformity introduces additional complexity in the implementation of conforming finite element formulations [3]. Despite the aforementioned, we note the following. First, the degree of implementation complexity is significantly reduced by enforcing the so-called 2:1 balance constraint, i.e., adjacent cells may differ at most by a single level of refinement; the -adaptive triangulation in GridapP4est.jl always satisfies this constraint. Second, Gridap is written such that it is entirely responsible for handling such complexity. As demonstrated in this tutorial, library users are not aware of mesh non-conformity when coding the weak form of the finite element formulation at hand.

It order to scale finite element simulations to large core counts, the adaptive mesh must be partitioned (distributed) among the parallel tasks such that each of these only holds a local portion of the global mesh. (The same requirement applies to the rest of data structures in the finite element simulation pipeline, i.e., finite element space, linear system, solver, etc.) Besides, as the solution might exhibit highly localized features, dynamic mesh adaptation can result in an unacceptable amount of load imbalance. Thus, it urges that the adaptive mesh data structure supports dynamic load-balancing, i.e., that it can be re-distributed among the parallel processes in the course of the simulation.

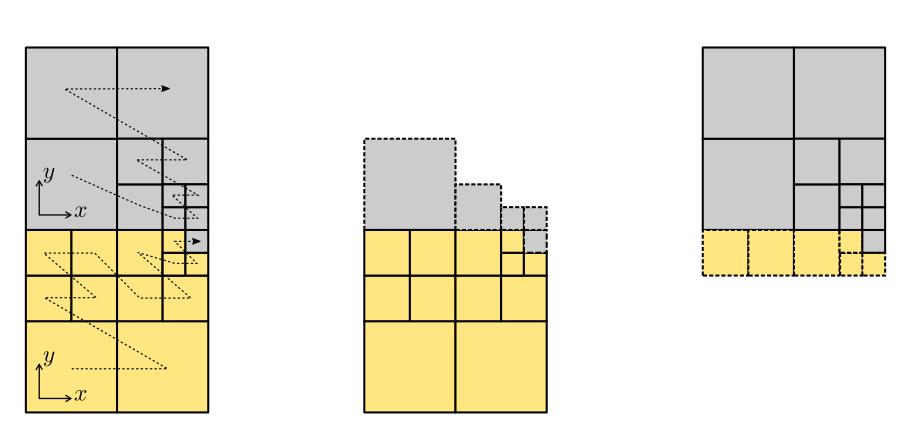

Modern forest-of-trees manipulation engines, such as p4est, provide a scalable, linear runtime solution to the mesh (re-)partitioning problem based on the exploitation of Space-Filling-Curves (SFCs). SFCs provide a natural means to assign an ordering of the forest-of-trees leaves, which is exploited for the parallel arrangement of data. For example, in GridapP4est.jl, the forest-of-octrees leaves are arranged in a global one-dimensional data array in increasing Morton index ordering. This ordering corresponds geometrically with the traversal of a -shaped SFC (a.k.a. Morton SFC). This approach allows for fast dynamic repartitioning. A partition of the mesh is simply generated by dividing the leaves in the linear ordering induced by the SFCs into as many equally-sized segments as parallel tasks involved in the computation.

As an illustration, the figure below shows a 2:1 balanced forest-of-quadtrees mesh with two quadtrees (i.e., ) distributed among two processors, 1:4 refinement and the Morton SFC. Local cells are depicted with continuous boundary lines, while those in the ghost layer with dashed ones.

GridapP4est.jl reconstructs the local portion of the mesh corresponding to each parallel task from the distributed forest-of-octrees that the p4est library handles internally. These local portions are illustrated in the figure above when the forest-of-octrees is distributed among two processors. The local portion of each task is composed by a set of cells that it owns, i.e., the local cells of the task, and a set of off-processor cells (owned by remote processors) which are in touch with its local cells, i.e., the ghost cells of the task. This overlapped mesh partition is used by the library to exchange data among nearest neighbours, and to glue together the global degrees-of-freedom of the finite element space which are sitting on the interface among subdomains, as required in order to construct finite element spaces for conforming finite element formulations in a distributed setting.

We first start as usual by importing the packages we will need:

using DrWatson

using Gridap

using PartitionedArrays

using GridapDistributed

using GridapP4est

using MPIThen we define the manufactured data for our problem, i.e., , , and the right hand side of the mass conservation equation:

γ, r, xc = 100.0, 0.7, VectorValue(-0.05, -0.05)

p_exact(x) = atan(γ * (sqrt((x[1] - xc[1])^2 + (x[2] - xc[2])^2) - r))

u_exact(x) = -∇(p_exact)(x)

f(x) = (∇⋅u_exact)(x)For convenience, we define a function solve_darcy which performs some of the steps of the finite element simulation pipeline (namely finite element spaces setup, assembly and solution of linear system). We will later re-use this function at at each mesh of the AMR hierarchy:

function solve_darcy(model,order)

V = FESpace(model,

ReferenceFE(raviart_thomas,Float64,order),

conformity=:Hdiv)

Q = FESpace(model,

ReferenceFE(lagrangian,Float64,order);

conformity=:L2)

U = TrialFESpace(V,u_exact)

P = TrialFESpace(Q)

Y = MultiFieldFESpace([V, Q])

X = MultiFieldFESpace([U, P])

trian = Triangulation(model)

degree = 2*(order+1)

dΩ = Measure(trian,degree)

Γ = BoundaryTriangulation(model)

dΓ = Measure(Γ,degree)

nΓ = get_normal_vector(Γ)

a((u, p),(v, q)) = ∫(u⋅v)dΩ +∫(q*(∇⋅u))dΩ-∫((∇⋅v)*p)dΩ

b((v, q)) = ∫(q*f)dΩ-∫((v⋅nΓ)*p_exact )dΓ

op = AffineFEOperator(a,b,X,Y)

xh = solve(op)

xh, num_free_dofs(Y)

endAt this point you should be already familiar with the steps in the solve_darcy function. It worths noting that we create V, i.e., the finite element space for the fluid velocity, such that it is div-conforming. To this end, as mentioned above, we use the raviart_thomas finite element, and specify the conformity of the space to be :Hdiv.

For convenience, we also define a function to compute the errors among the finite element solution and the exact solution. We will be also using the function at each level of the AMR hierarchy.

function compute_error_darcy(model,order,xh)

Ω = Triangulation(model)

degree = 4*(order+1)

dΩ = Measure(Ω,degree)

Γ = BoundaryTriangulation(model)

degree = 2*(order+1)

dΓ = Measure(Γ,degree)

nΓ = get_normal_vector(Γ)

uh, ph = xh

eu = u_exact - uh

ep = p_exact - ph

l2_norm(v) = sqrt(sum(∫(v⋅v)dΩ))

hdiv_norm(v) = sqrt(sum(∫(v⋅v + (∇⋅v)*(∇⋅v))dΩ))

l2_norm(eu), hdiv_norm(eu), l2_norm(ep)

endFor visualization purposes, we define a function which, given a distributed discrete model, returns a distributed cell array which contains the parallel task identifier that owns each cell. If we visualize such array in ParaView, we will be able to observe how the mesh has been partitioned among parallel tasks

function get_cell_to_parallel_task(model)

model_partition_descriptor=partition(get_cell_gids(model))

map(model_partition_descriptor) do indices

own_to_owner(indices)

end

endThe next step is to create the coarse mesh . As is just the unit square in our particular case, a CartesianDiscreteModel with a single cell is sufficient to resolve the geometry of :

coarse_model=CartesianDiscreteModel((0,1,0,1),(1,1))We stress, however, that we may import as well a coarse mesh generated from an unstructured mesh generator, e.g., using GridapGmsh, as we have done in other tutorials.

As with any parallel distributed memory code in the Gridap ecosystem, we have to create our distributed rank indices. Using the MPI julia package, we can query for the number of MPI tasks with which we spawned the parallel program. In particular, the MPI.Comm_size function provides such functionality.

MPI.Init()

nprocs = MPI.Comm_size(MPI.COMM_WORLD)

ranks = with_mpi() do distribute

distribute(LinearIndices((prod(nprocs),)))

endOnce we have created the coarse mesh and the rank indices, we are ready to create the forest-of-quadtrees DiscreteModel. We do it by specifying how many steps of uniform refinement steps we want to apply to the coarse mesh. We note that the resulting mesh is already distributed/partitioned among the parallel tasks:

num_uniform_refinement_steps=4

model=OctreeDistributedDiscreteModel(ranks,coarse_model,num_uniform_refinement_steps)Once we have created an inital forest-of-quadtrees, we will dynamically build a hierarchy of successively adapted meshes by exploiting the knowledge of the approximate solution computed at each level. This iterative process, which we will refer to as AMR loop, can be summarized as follows:

Compute an approximate finite element solution for the Darcy problem using the current mesh.

Compute for all cells in the mesh using . In general, is an error indicator such as, e.g., an a-posteriori error estimator [4]. In this particular tutorial, as we know the true solution , we will use the true error norm instead.

Given user-defined refinement and coarsening fractions, denoted by and , resp., find thresholds and such that the number of cells with (resp., ) is (approximately) a fraction (resp., ) of the number of cells in the mesh.

Refine and coarsen the mesh cells, i.e., generate a new mesh, accordingly to the input provided by the previous step.

(Optionally) Dynamically balance load among the parallel tasks.

Repeat steps 1.-5. a number of user-defined steps.

This algorithm is encompassed in the amr_loop function below:

function amr_loop(model, order, num_amr_steps, αr, αc;

generate_vtk_files=true, redistribute_load=true)

adaptive_strategy=

FixedFractionAdaptiveFlagsMarkingStrategy(αr, αc)

ndofs_x_level=Int[]

l2eu_x_level=Float64[]

hdiveu_x_level=Float64[]

l2pe_x_level=Float64[]

dir = datadir("darcy-amr")

i_am_main(ranks) && !isdir(dir) && mkdir(dir)

for amr_step = 0:num_amr_steps

# Solve the finite element problem in the current mesh

xh,ndofs = solve_darcy(model,order)

if (generate_vtk_files)

file = dir*"/results_amr_order=$(order)_step_$(amr_step)"

uh,ph = xh

writevtk(Triangulation(model),

file,

cellfields=["uh"=>uh,

"ph"=>ph,

"euh"=>u_exact-uh,

"eph"=>p_exact-ph,

"partition"=>get_cell_to_parallel_task(model)])

end

# Compute error among finite element solution and exact solution

l2eu,hdiveu,l2ep=compute_error_darcy(model,order,xh)

append!(l2eu_x_level,l2eu)

append!(hdiveu_x_level,hdiveu)

append!(l2pe_x_level,l2ep)

append!(ndofs_x_level,ndofs)

# Compute error indicators e_K

uh,ph = xh

euh = u_exact-uh

eph = p_exact-ph

Ω = Triangulation(model)

dΩ = Measure(Ω,2*order+1)

e_K = map(dc -> sqrt.(get_array(dc)), local_views(∫(euh⋅euh)dΩ))

# Get object which describes how the mesh is partitioned/distributed among parallel tasks

model_partition_descriptor=partition(get_cell_gids(model))

# Create/initialize adaptivity flags

ref_coarse_flags = map(model_partition_descriptor) do indices

flags = Vector{Int64}(undef, length(indices))

flags .= nothing_flag

end

# Determine which cells are marked for refinement/coarsening

update_adaptivity_flags!(ref_coarse_flags,

adaptive_strategy,

model_partition_descriptor,

e_K)

# Adapt the model given the adaptivity flags

model,_= adapt(model, ref_coarse_flags)

if (amr_step != num_amr_steps && redistribute_load)

# Dynamically redistribute the model among parallel tasks

model,_= redistribute(model)

end

end

model,ndofs_x_level,l2eu_x_level,hdiveu_x_level,l2pe_x_level

endThe amr_loop function re-uses the previously defined functions along with functionality available in GridapP4est.jl to implement the 6 steps enumerated above. The FixedFractionAdaptiveFlagsMarkingStrategy constructor creates a Julia object which conceptually represents the strategy in step 3. Combining this object with the cell-wise error indicators , the update_adaptivity_flags! function determines which cells to be refined, which to coarsen, and which to leave as they were prior to adaptation (as per described in step 3.). Finally, the adapt function adapts the mesh using the flags, and the redistribute function dynamically balances the load among the MPI tasks to correct for the imbalances caused by mesh adaptation.

It is worth noting that both the adapt and redistribute functions return a second object apart from the transformed discrete model. These objects are referenced by a place holder variable named _ which is not further used in the function. We note, however, that these objects encode relevant information that allows one to describe how the original and the transformed models are related. This is particularly necessary when dealing with transient and/or non-linear problems, where one has to transfer data (e.g., finite element functions) among meshes. For simplicity, this feature is not illustrated in the tutorial.

We then call the amr_loop function with αr=0.1 and αc=0.05 meaning that approximately 15% and 5% of the cells will approximately be refined and coarsened, respectively, at each adaptation step.

order=1

αr=0.10

αc=0.05

num_amr_steps=10

final_model,ndofss,l2ues,hdivues,l2pes=amr_loop(model, order, num_amr_steps, αr, αc;

generate_vtk_files=true, redistribute_load=true)After execution, the function generates data visualization files plus the L2 and Hdiv errors of the discrete fluid flow and the L2 error of the discrete fluid velocity at each AMR level. At this point, we encourage the reader to open these files in ParaView and observe that, as expected, there is a clear tendency of the algorithm to adapt the mesh in the region where the circular wave front is located. The reader may also want to observe how the partition of the mesh among cells varies among levels in order to correct for the parallel load imbalances caused by mesh adaptation.

As usual, it is helpful to visualize how errors decay with the number of degrees of freedom as the mesh is adapted across several adaptation cycles. The following code generates a plot and writes it into a PDF file in the parallel task with identifier 0.

if i_am_main(ranks)

using Plots

plt = plot(xlabel="ndofs",ylabel="L2 error (fluid velocity)",grid=true)

plot!(plt,title="γ=$(γ), r=$(r), center=$(xc)", yaxis=:log10, xaxis=:log10, linewidth=3)

plot!(plt,ndofss,l2ues,label="order=$(order) AMR",markershape=:s,markersize=6)

dir = datadir("darcy-amr")

!isdir(dir) && mkdir(dir)

filename = datadir("darcy-amr/amr_error_decay_l2eu_order=$(order).pdf")

savefig(plt, filename)

endDeactivate redistributed_load in the amr_loop function call. Then, observe in ParaView the load distribution among parallel tasks, and compare it against the one in which the load is re-balanced at each step.

Extend the code such that it compares error decay between uniform refinement and AMR.

Study error decay of order=0 versus order=1.

Study error decay and refinement patterns for different values of , , .

Extend the present tutorial to 3D.

[1] F. Brezzi and M. Fortin. Mixed and hybrid finite element methods. Springer-Verlag, 1991.

[2] C. Burstedde, L. C. Wilcox, O. Ghattas. p4est: Scalable Algorithms for Parallel Adaptive Mesh Refinement on Forests of Octrees. SIAM Journal on Scientific Computing 33 (3) (2011).

[3] S. Badia, A. F. Martin, E. Neiva, and F. Verdugo. A Generic Finite Element Framework on Parallel Tree-Based Adaptive Meshes. SIAM Journal on Scientific Computing 46 (2) (2020).

[4] M. Ainsworth, J. T. Oden. A Posteriori Error Estimation in Finite Element Analysis.. John Wiley & Sons, 2000.